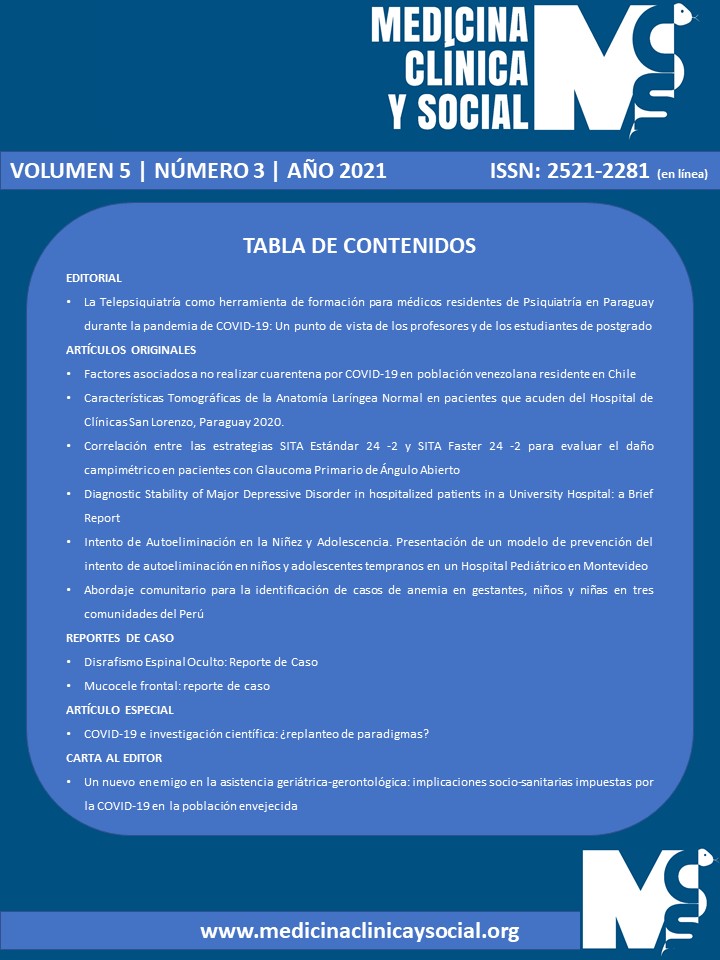

Español Español

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.52379/mcs.v5i3.180Keywords:

Cuarentena, Infecciones por Coronavirus, Migrantes, Condiciones de Trabajo, Beneficios en salud, Pandemia, Salud públicaAbstract

Introduction: Venezuelan immigrants residing in Chile have increased not only in quantity, but also in the vulnerability in which they migrate. Therefore, it becomes relevant to understand how they carried out one of the most promulgated care measures to COVID-19 propagation: compliance quarantine. Objective: Analyze which elements made it difficult to carry out quarantine in the Venezuelan population residing in Chile, since confinement is one of the most promulgated measures to protect the population from the spread of COVID-19. Methodology: We conducted an observational quantitative cross-sectional study based on an online survey on COVID-19 among international migrants living in Chile, carried out in April 2020, through a “snowball” sampling strategy (n=1,690 migrants). This secondary analysis is focused on Venezuelan participants (N=1,006), through descriptive, bivariate and multivariate regression analyses, with Raking adjustment to reduce self-selection bias. Results: The chances of non-compliance the quarantine recommendation are higher in those who have job ([OR=5,35, 95%IC [3,16-9,02]), in relation to those who do not; in those who not have a have a health plan ([OR=4,02, 95%IC [1,57-10,32]), and those who have public plan (Fonasa) ([OR=3,92, 95%IC [1,84-8,35]), in relation to people with private health insurance; in men ([OR=2,23, 95%IC [1,50-3,32]) than in women; and in those with a lower education level at a higher lever ([OR=1,74, 95%IC [11,50-3,32]). Conclusions: The association between not complying with quarantine and working conditions and type of health insurance, exposes the relevance of socioeconomic vulnerability in the opportunities to carry out public health care measures in the Venezuelan migrant population in Chile, such as the monitoring of confinement during a pandemic like COVID-19. This is important for health planning in future socio-health crises.

Downloads

References

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Departamento de Extranjería y Migración. Estimación de personas extranjeras residentes habituales en Chile al 31 de Diciembre de 2019 [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://bit.ly/3pj7jTE

Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes. Dinámicas fronterizas en el norte de Chile el año 2020: Pandemia, medidas administrativas y vulnerabilidad migratoria [Internet]. 2020. Report No.: 5. Available from: https://bit.ly/3aJ3zqx

Cao Y, Liu R, Qi W, Wen J. Spatial heterogeneity of housing space consumption in urban China: Locals vs. inter-and intra-provincial migrants. Sustainability. 2020;12(12):1–26.

Koh D. Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:634–6.

Ramírez-Cervantes KL, Romero-Pardo V, Pérez-Tovar C, Martínez-Alés G, Quintana-Diaz M. A medicalized hotel as a public health resource for the containment of Covid-19: more than a place for quarantining. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2020;1–14.

Poole DN, Escudero DJ, Gostin LO, Leblang D, Talbot EA. Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in complex humanitarian crises. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–3.

Cabieses B. Salud y migración: un proceso complejo y multidimensional. In: Rojas Pedemonte N, Vicuña JT, editors. Migración en Chile: Evidencias y mitos de una nueva realidad. Santiago de Chile: LOM ediciones; 2019. p. 400.

Benítez A, Velasco C. Desigualdades en salud: Brechas en acceso y uso entre locales e inmigrantes. In: Aninat I, Vergara R, editors. Inmigración en Chile Una mirada multidimensional. Santiago de Chile: Fondo de Cultura Económica; 2019. p. 191–235.

Cotlear D, Gómez-Dantés O, Knaul F, Atun R, Barreto ICHC, Cetrángolo O, et al. La lucha contra la segregación social en la atención de salud en América Latina. MEDICC Rev. 2015;17:S40–52.

Expósito F, Lobos C, Roessler P. Educación, formación y trabajo: barreras para la inclusión en migrantes. In: Rojas Pedemonte N, Vicuña JT, editors. Migración en Chile: Evidencias y mitos de una nueva realidad. Santiago de Chile: LOM ediciones; 2019. p. 107–42.

Bravo J. Mitos y realidades sobre el empleo en Chile. In: Rojas Pedemonte N, Vicuña JT, editors. Migración en Chile: Evidencias y mitos de una nueva realidad. Santiago de Chile: LOM ediciones; 2019. p. 49–72.

ICIM, Colegio Médico de Chile, Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes, MICROB-R. Encuesta Sobre Covid-19 a Poblaciones Migrantes Internacionales En Chile [Internet]. Santiago de Chile; 2020. Available from: https://bit.ly/38BkWXE

Aglipay M, Wylie JL, Jolly AM. Health research among hard-to-reach people: Six degrees of sampling. CMAJ. 2015;187(15):1145–9.

Faugier J, Sargeant M. Sampling hard to reach populations. J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(4):790–7.

Mercer A, Lau A, Kennedy C. For Weighting Online Opt-In Samples, What Matters Most? [Internet]. Pew Research Center. 2018. Available from: https://pewrsr.ch/3heqknn

Powers DA, Xie Y. Statistical Methods for Categorical Data Analysis. London, England: Academic Press, Inc; 2000. 295 p.

Agresti A, Finlay B. Statistical Methods for Social Sciences. New Yersey, USA: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009. 595 p.

Stefoni C, Bonhomme M. Una vida en Chile y seguir siendo extranjeros. Si somos Am Rev Estud Transfront. 2014;14(2):81–101.

Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes. Criminalidad, Seguridad y Migración: Un análisis en el Chile actual [Internet]. Santiago de Chile; 2020. Report No.: 4. Available from: https://bit.ly/2JdNA8j

Fadnes LT, Møen KA, Diaz E. Primary healthcare usage and morbidity among immigrant children compared with non-immigrant children: A population-based study in Norway. BMJ Open. 2016;10(6):1–8.

Hasanali S. Immigrant-Native Disparities in Perceived and Actual Met/Unmet Need for Medical Care. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2015;17(5):1337–46.

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Pablo Ignacio Roessler Vergara, Tomás Soto Ramírez, Báltica Cabieses

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.